In our high-speed and high-tech world, walking has sadly and unfortunately fallen out of favor. “Pedestrian” is almost derogatory – a euphemism for something prosaic, rather ordinary and commonplace. Yet, walking with intention, walking for a purpose has deep roots. Australia’s aborigines walk during rites of passage, while Native Americans conduct vision quests in the wilderness; for many centuries, millenia perhaps, people have walked the Camino de Santiago, which spans across the breadth of Spain. I recollect having read someplace: All these pilgrims place one foot firmly in front of the other, to fall in step with the rhythms of the universe and the cadence of their own hearts. As one foot walks, the other rests. The fact of doing and being comes into balance. Remember “The Pilgrim’s Progress” written by John Bunyan?

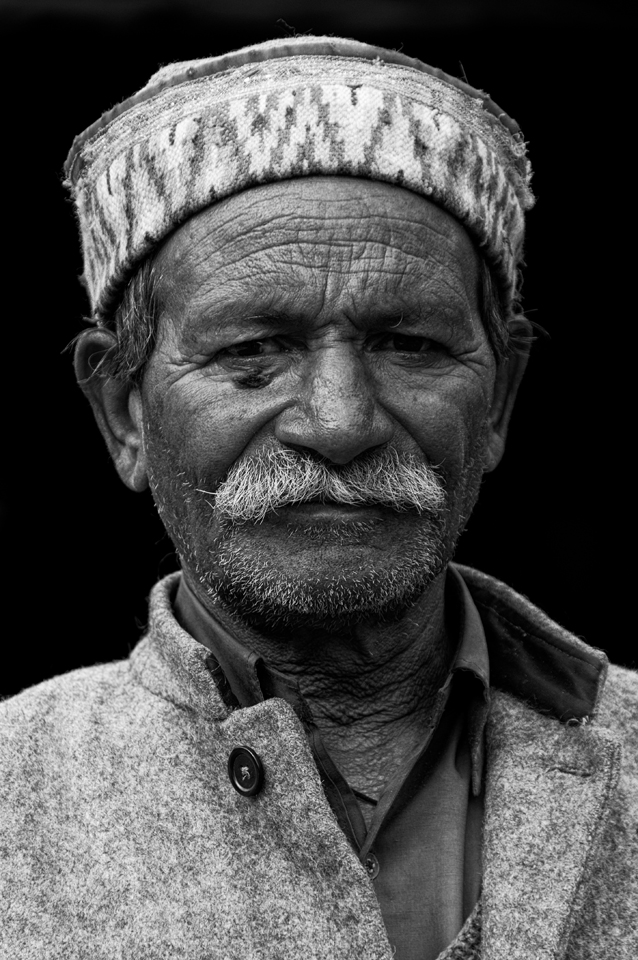

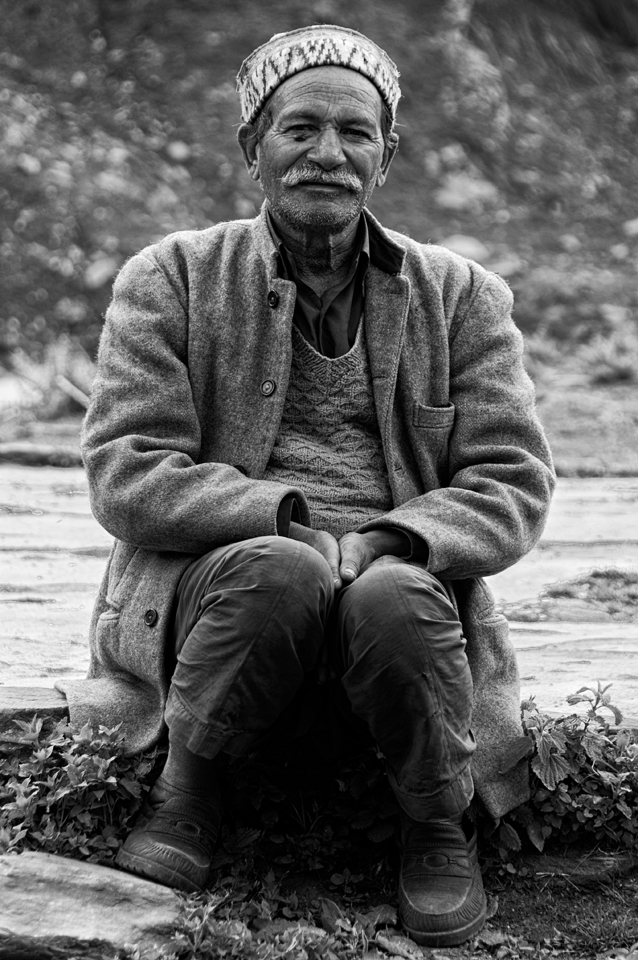

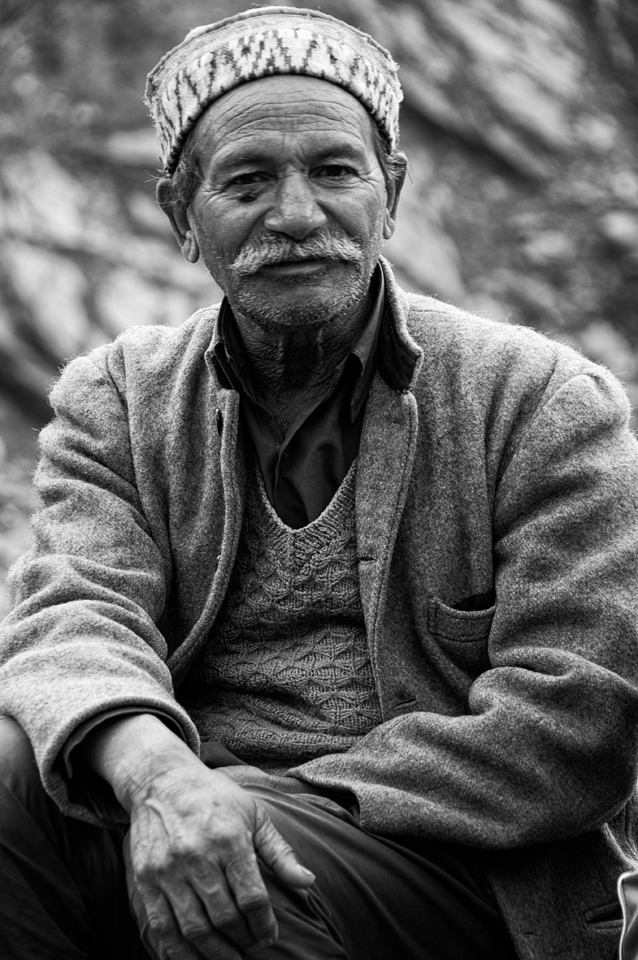

I am one such pedestrian, one such pilgrim, and I am just back from walking in the Himalayas across a week and more, where I met another pedestrian, albeit slightly different. This is the story of Dighti Ram, a shepherd. At about sunset, I saw him standing in front of his dilapidated stone wall-and-tin roof shed staring out at the pasture; having nothing left to do but settle into my tent for the night, I walked up to him to see if he’d agree for me to make a few photographs with him. As I usually always do with the people I photograph, I chatted with him for a while even before I pressed the shutter. Why do I talk to people before I photograph them? One for reasons of photography: it puts them at ease and makes for more natural portraits, and two for selfish, personal reasons: always, each and every time without fail, I have walked away from such conversations with “so-called ordinary” people having (re)learnt invaluable, indelible lessons of life.

Dighli Ram is a 69 year old man who has tended to his goats and sheep across the last six decades in the sometimes verdant, mostly freezing, but always beautiful mountains of the Dhauladhar, the outermost fringe of the Himalayas. He has about 300 goats and 400 sheep, large tracts of farmland, and a house leased to a company, bringing his net worth to $120,000, wealthy by any standards in India. But this isn’t about Dighti Ram’s balance sheet or his assets – I’m just putting elements into context. As we got conversing, I questioned if he ever got tired of doing the same thing day-after-day, walking the same stretch of land for sixty years, or for that matter did he compel himself to do it so that he could get more wealth, more property? His answer was to quote the Bhagavad Gita: “To action alone hast thou a right and never at all to its fruits; let not the fruits of action be thy motive; neither let there be in thee any attachment to inaction.” Lesson #1.

He invited me into his shed to share a cup of tea, and later made me promise to come and stay at his farm whenever I am there next – a promise I shall abide by. Now Dighti Ram didn’t invite me because he assessed me by my business card, my professional network on LinkedIN or my salary. His innate simplicity allowed him to invite me without questioning: “What’s in it for me?” Most of us believe that to give, we first need to have something to give. This is paradoxical and the trouble with that is, as Oscar Wilde once said, “Nowadays, people know the price of everything, but the value of nothing.” We have forgotten how to value things which don’t have a price tag – things (or feelings) such as empathy and care and compassion and love. When I’m reminded of this, I realize that true generosity doesn’t start when I have something to give, but rather when there’s nothing in me that’s trying to take. The more I am with such people, the more I learn to love unconditionally. In our dominant paradigm, Hollywood has insidiously co-opted the word, but the love I’m talking about here is the kind of love that only knows one thing – to give with no strings attached. Purely. Selflessly. Lesson #2.

His face lit up as he, the proud father, told me of his sons – one a shepherd like him and the other a TV-and-radio technician. Then with a forlorn, longing, faraway expression he told me of his wife who tends to the farm and harvest all alone, as he roams with the herd in search of pastures and how he misses her whenever he is away even at this age (which of course was utterly romantic). It reminded me of Kuan Tao-Sheng’s evocative and expressive words: “ You and I have so much love, That it burns like a fire, In which we bake a lump of clay, Molded into a figure of you and a figure of me. Then we take both of them and break them into pieces, And mix the pieces with water, And mold again a figure of you and a figure of me. I am in your clay, You are in my clay. In life we share a single quilt. In death we will share one coffin.” Yes, for all of us, our love, our happiness, our pride is alike; we share the same fears, cry the same tears. The more I spoke with him, the more I became convinced how in the tangle and weave, warp and weft of the Universe, we are all different yet just the same. Lesson #3.

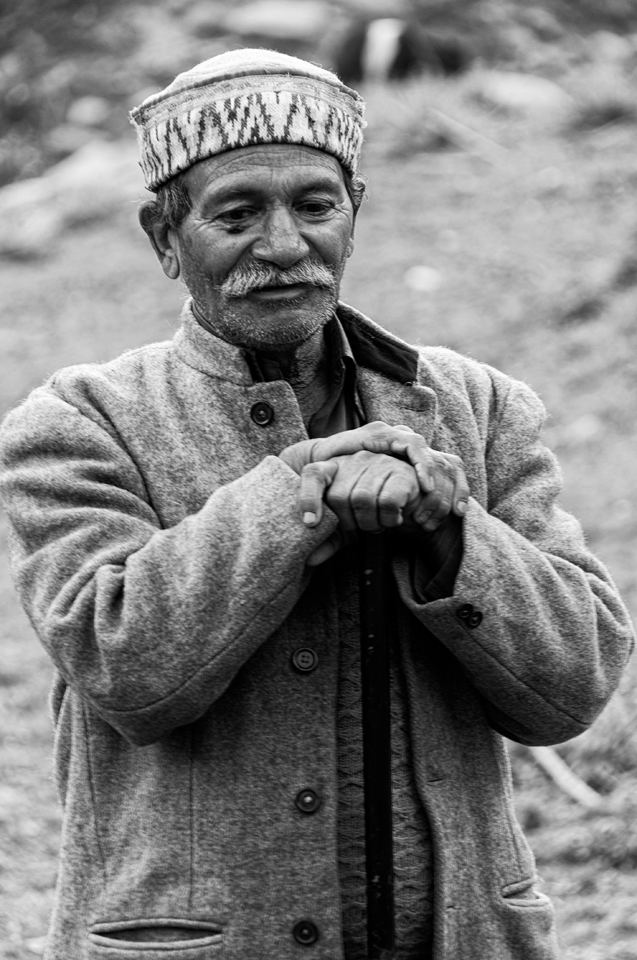

Somewhere down the line in the course of our conversation, we started talking about wildlife in the mountains and he told me of the number of times he had sighted bears and leopards. So I asked if his herd had ever targeted by wild animals to which he said: “Yes, but I am safe as I have a rifle” upon which he proudly brought out a battered and bruised worn-leather rifle case, assembled his rifle and posed with it.

My smartass attitude got the better of me and I said: “But do you really think this small-caliber, muzzle-loading rifle is good enough to protect you against mountain bears or leopards?” – to that he just smiled at my ignorance, looked down at the ground briefly and then to the sky for a bit, and said softly almost in a whisper, “But He is always there for me.” Which is when the 23rd Psalm of the Old Testament came to my mind:

“The Lord is my Shepherd; I shall not want.

He maketh me to lie down in green pastures: He leadeth me beside the still waters.

He restoreth my soul: He leadeth me in the paths of righteousness for His name’s sake.

Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me.”

So thank you Mr. Shepherd, for reminding me:

“The Lord is my Shepherd”.

Leave a Reply